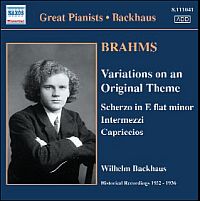

|  Brahms Piano Works - Wilhelm Backhaus Brahms Piano Works - Wilhelm Backhaus

Scherzo Op 4,

Variations Op 21,

Waltzes Op 39 Nos 1, 2, 15,

Pieces Op 76 Nos 2, 7, 8

Op 116 No 1, 2, 4,

Op 117 No 1, 2,

Op 118 Nos 1-6,

Op 119 Nos 1-3

Naxos historical 8.11041 This is some of the best Brahms playing you will hear, breathtaking in its spontaneity and imagination. Backhaus' great compatriot and contemporary, Wilhelm Kempff, was equally natural and poetic in his well-regarded interpretations of Brahms (notably in recordings from the fifties), but his records do not have Backhaus' sense of improvisatory freedom. I guarantee you will hear Brahms with new ears, the composer's crusty academic correctness utterly subsumed in a sense of poetic flow.

It is easy to play Brahms badly, to make it sound turgid, or monotonous, or sentimental. Backhaus avoids every trap, even bringing the utmost clarity to thick textures (such as in 118/4 or119/3). The subtlety of his rubato, speeding up a fraction to avoid an overplus of sentiment (as in 117/1 or 118/2, but always with a perfect underlying awareness of the rhythmical pulse allows the utmost expressivity without any sense of exaggeration. We hear late Brahms, therefore, with all the energy and fervour of the first piano concerto or the string sextets; at the same time, we feel the loneliness (116/4) or regret (116/2) that make him the most world-weary of all composers. Even 119/1, a tremendously difficult piece to bring off musically, submits to a very slow tempo without the least sense of being static. There may be moments of instability, such as the opening of Op 116/1, but these are invariably compensated for by the immense sensitivity of the trio sections and reprises, especially in pianissimo and una corda (not only 116/1, but also 118/3, for example).

Those like me who remember Wilhelm Backhaus as an old pianist (for example, his last recital is available on an Italian radio / Decca CD), forget the athletic virtuosity of his youth. He was indeed, especially known for his Brahms. The early Scherzo is precise and heroic, a youthful quest, the rarely-heard Op 21 Variations a model of strong structural awareness. Backhaus passes the hardest test, to make pieces so well known that they are hackneyed (No 15, the best-known of the Op 39 waltzes and Op 118/2, beloved of a thousand salons) sound both fresh and simple. Backhaus' lack of affectation always triumphs.

The high transfer quality of the Naxos historical series is frequently commented on. These are recordings from 1932-6, remarkable for Backhaus' lack of wrong notes in an era when editing was barely done, but also for the fidelity of the recorded sound. Altogether an exquisite disc. © Ying Chang

|