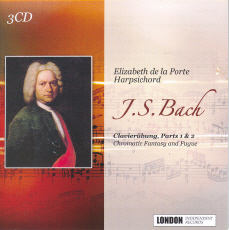

|  J S Bach Clavieruebungen parts 1 and 2 J S Bach Clavieruebungen parts 1 and 2

6 Partitas, Italian Concerto, French overture, Chromatic Fantasia and Fugue

Elizabeth de la Porte (harpsichord)

London Independent Records LR012

(Previously released on Saga and Hyperion)

The interpretation of composers of the Classical and Romantic periods does not ‘progress.' We still aspire to play Beethoven as well as Gilels did, or Chopin as the young Pollini. But with the Baroque period, the authenticity movement has caused there to be a complicated and multi-dimensional evolution in how we interpret Bach. It's not that we are ‘right' now and wrong ‘then'; we have simply become more ambitious and various in what is allowed without seeming unfaithful to the text. Thirty or forty years ago, to play ‘authentically' at all was itself a risk.

So what happens when we hear this solid and worthy private re-issue of seventies' LP recordings, extremely plain, straight readings of Clavieruebungen 1 and 2? Although the booklet apologises for deficiencies in the transfer, the sound is fine and natural - no problems at all for the listener. The problem, rather, is with de la Porte's playing, which sounds dated without being (yet?) of historical value.

When the booklet says de la Porte puts drama and poetry above academic correctness, this may be a justified apologia for performance first, scholarship second. But it is not what one actually hears these days. It is accepted, as well as fashionable, that today's Bach has more emotional freedom, simply more lightness. What may have seemed (when these recordings were made in 1973-5) freshness and essence on original instruments, a commendable exposition and a new insight on an old century, now seems extraordinarily uniform, even laboured. In particular, there is an extraordinarily strong emphasis on each beat which gives every single movement a static, unvaried, sowing-machine quality. It is a world apart from Trevor Pinnock, Ronald Brautigam or Richard Goode, to name proponents of three different types of instrument.

The unnatural characteristics of the recording (one manual comes out of one speaker, the other from the other; one listens as if inside the instrument) may also have contributed to the original Hyperion Partitas issue's disappearance (the other pieces were on Saga, where the label itself is defunct).

De la Porte still has her followers; but it is frustrating not to be able to hear her thoughts on these pieces now, rather than CDs that seem pedantic and anachronistic without being especially original.

Ying Chang

A reader's response:

Re Ying Chang's review of re-issued recordings by Elizabeth de la Porte:

Elizabeth de la Porte's first recordings of Bach were released in the mid-1970s, followed by a complete recording of the six Partitas (BWV 825-30) on Hyperion some years later. It was obvious that she was a musician of extraordinary accomplishment. Her sense of rhythm and timing, her feel for phrasing, her judicious sense of tempo and her fine touch and sense of colour marked her out as a harpsichordist of the very first rank. It is astonishing to read a review of this great artists that essentially dismisses her art as unworthy of notice. Reviews can sometimes tell us more about a reviewer's expectation or experience than they do about the work being reviewed. In this case, Ms. de la Porte has been very badly served.

When the booklet says de la Porte puts drama and poetry above academic correctness, this may be a justified apologia for performance first, scholarship second. But it is not what one actually hears these days. It is accepted, as well as fashionable, that today's Bach has more emotional freedom, simply more lightness. What may have seemed (when these recordings were made in 1973-5) freshness and essence on original instruments, a commendable exposition and a new insight on an old century, now seems extraordinarily uniform, even laboured. In particular, there is an extraordinarily strong emphasis on each beat which gives every single movement a static, unvaried, sowing-machine quality. It is a world apart from Trevor Pinnock, Ronald Brautigam or Richard Goode, to name proponents of three different types of instrument.

Your reviewer has missed the point: what is often touted these days – mistakenly – is that Bach was just another German composer imitating the French or Italian manner, rather than the supreme musician who understood all styles and transcended them in the creation of his own works. His works are, as a result, often trivialized in performances that pay no heed to what really makes his music important. Ms de la Porte's playing conjures more emotional freedom than most harpsichordists can even imagine, while her use of accents is derived from the nature of the consonant-rich German language itself, which was one of the principal elements in Bach's musical thought. Bach's music calls for far more than just "lightness" – one cannot describe the universe using one single aspect of its creative potential. It contains everything and requires an astonishing range of touch, phrasing and emotional affect (freedom of emotion) to be realised properly – precisely what Ms. de la Porte provides, in fact, while many of today's performers do not. Your reviewer also never makes clear how "scholarship" relates automatically to "emotional freedom" or "more lightness", when these aspects actually have no inevitable connection at all. For years, in fact, mention of so-called "scholarship" in performance was usually an admission of dullness and lack of imagination. Great musicians are usually knowledgeable – whether in a scholarly or more intuitive way is not always important. Elizabeth de la Porte certainly knows a great deal about the harpsichord, the music and how to play it. Is this sufficient to be termed "scholarship"? What else is necessary?

What one rarely hears today on the harpsichord is an effective combination of musicianship, taste, restraint - yes, and scholarship – that is truly capable of shedding new light on Bach's timeless masterpieces. Only a few harpsichordists over the past 100 years - Wanda Landowska, Isolde Ahlgrimm and Gustav Leonhardt among them – have been able to do this. These three very different artists show how alternate, yet valid conclusions can be drawn by looking at the same material. Elizabeth de la Porte is another member of this elite, entirely worthy to stand in their company, even on the basis of the handful of recordings she has so far been able to make. I find it interesting to find her work compared to that of players like Trevor Pinnock (whose career began around the same time as hers) and judged inferior (the other artists your reviewer listed are pianists - and any valid basis of comparison here entirely escapes me). Indeed, the description of Ms. de la Porte's playing as conveying "a static, unvaried, sewing-machine quality" sounds far more like a description of some of Trevor Pinnock's recordings from this period (the Bach Toccatas for Archiv, for example), which were indeed pretty relentless – which is the antithesis of Ms. de la Porte's own playing.

Your reviewer has it backwards, I'm afraid, while the assertion that somehow the 1970s were the dark ages of historical performance is also wrong. That landscape was populated by musicians at the height of their powers such as Gustav Leonhardt, Isolde Ahlgrimm. Jaap Schröder, David Munrow, Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Frans Brüggen, Thomas Binkley, Max van Egmond – the list is endless. Today's younger musicians would do well to go back and study those things that inspired us all to undertake the study of period instruments to which they are heirs. My interaction with younger musicians playing "old" instruments today suggests that they have often forgotten why they are interested in historical performance at all, or why it is important to know more about music than what is simply printed in the score. A mature musical culture honours its great representatives of all periods – it does not dismiss or disparage them.

Every reviewer is entitled to an opinion. My own is based on thirty-five years experience as a prominent professional harpsichordist who is today fortunate to be known as a ranking specialist in Bach's music. I am one of Ms. de la Porte's younger colleagues who was – in the mid 1970s – greatly inspired by her own example. I am intimately familiar with all the potential rewards and pitfalls of a so-called "historically informed" approach to playing music. I also know that this quest for a Holy Grail of historical truth is basically an illusion. What remains timelessly true is that there is no substitute for great musicianship in the service of music that is better than it can be played – to quote Ralph Kirkpatrick.

Under no circumstances could I allow this incorrect and dismissive view of the work of one of our very great artists to go unchallenged. Lovers of Bach and the harpsichord should re-investigate Elizabeth de la Porte's art forthwith. I certainly will.

Peter Watchorn

Dear Editor:

I am all for opinions divergent from my own to be published and placed directly against my own. - - On two points I do clearly disagree; one, I think it is legitimate to discuss different interpretations of the same music played on different instruments. Two, I simply don't hear what he does in Elizabeth de la Porte's playing, which I found very ordinary. Specifically, rather than find her playing emotionally interesting (as Mr Watchorn does and the liner notes to her discs enjoin the listener to do) I found it the opposite; too pedgaogic - - more contributions from Mr Watchorn to MP would be welcome, and I would be glad of rebuttals of any of my real opinions. YC

A further review sent to us in riposte to YC's [Editor, August 2008] :-

- - These wonderful recordings were made in 1973 and 1975 - - a matter for joy that they have come back after so long - - The notes on the works show Elizabeth de la Porte to be as gifted at communicating in words as she is at the keyboard. If there is anything that could possibly be called old-fashioned about these performances it is the evident warmth of feeling, something that is notoriously difficult to convey on the harpsichord- - De La Porte is mistress of subtly applied rubato - - the instrument she plays on is notably bright and full in tone. - - It is de la Porte’s devotion to this music which makes listening to her account so wholesome an experience, and one which improves I have found, with every repetition - - MT

[IRR Sept 2007]

|